By Scott Morgensen, Unsettling Ourselves

By Scott Morgensen, Unsettling Ourselves

My presentation to the Dakota Decolonization class echoed my broader teaching and writing by centering the principles of Indigenous feminist thought and its ties to women of color and Third World feminism. Andrea Smith in her book Conquest: Sexual Violence and American Indian Genocide (2005) writes that colonization and heteropatriarchy inherently interlink, so that opposition to one requires opposition to the other. Her Indigenous feminist argument links to the principle of intersectionality in women of color and Third World feminisms, which appears in the Combahee River Collective’s “A Black Feminist Statement” (1977) in the claim that “all the major systems of oppression are interlocking.”

I learned to commit to these principles by investigating and challenging the power and privilege that structure my life as a white, educationally-privileged, US American male, non-transgender and (temporarily) able-bodied. My lifelong experience as a queer person who has suffered from heteropatriarchy did teach me about oppression and resistance, as did my family’s struggles with work and income. But given my social locations, those experiences were not sufficient to teach me that colonization is the condition of heteropatriarchy and capitalism in the U.S., or that all the major systems of oppression intersect. Learning this required being challenged by Indigenous and women of color and Third World feminists to study how colonization, whiteness and racism, capitalism, ableism, and heteropatriarchy interlink in the world and in my life. Such an understanding contextualizes all my words about settlers and settlement.

My writing critically investigates the desires of settlers to feel connected to Indigenous land and culture. In her contribution to this sourcebook, Waziyatawin discusses Albert Memmi’s distinction of the colonizer and the colonized. I intend my use of the term “settler” to be compatible with Memmi’s term “colonizer” and with its discussion by Waziyatawin. “Settler” is a way to describe colonizers that highlights their desires to be emplaced on Indigenous land. The settler desires I study are not tied to any particular politics. Among settlers, “conservatives,” “liberals,” and “radicals” (to name only a few) share similar desires that simply express in varied ways. For instance, settler radicals, including anarchists, have proven capable of forming movements that profess to be anticolonial even as they claim Indigenous land and culture as their own. I recognize among settler radicals a difference between those who pursue a politics that tries to sustain their ties to Indigenous land and culture, and those who question any desire to possess them. I promote the latter in this essay as a way to radicalize settlers to challenge settler colonialism and support Indigenous decolonization.

I argue that critical reflection on settler desires for Indigenous land and culture will be crucial to any effort by settlers to ally with Indigenous decolonization struggles. I invite settlers to ask: How do their desires for Indigenous land and culture express colonization and contradict efforts to support Indigenous decolonization? How can settlers question their desires for Indigenous land and culture as a basis of committing to decolonization? Settlers can study every attachment they have felt to Indigenous land and ask how those relate to colonization. Historically, a desire to live on Indigenous land and to feel connected to it–bodily, emotionally, spiritually–has been the normative formation of settlers. Settler radicals who commit to Indigenous decolonization must act differently. Is it possible, at once, for settlers to wish to live on or feel linked to Indigenous land, and to act in support of decolonization? Should settler radicals first commit to be willing to no longer live on Indigenous land or have any connection to it, as part of fully committing to work for decolonization? Note that my questions do not dictate answers to how settlers’ lives will appear after pursuing such work. I merely insist that asking such questions define how settlers begin such work, so that they inform what comes after. How can settler radicals commit to be ready to no longer live on Indigenous land, or to have any connection to it as part of joining work for decolonization? How would settler radicalism appear differently if this question were central to it?

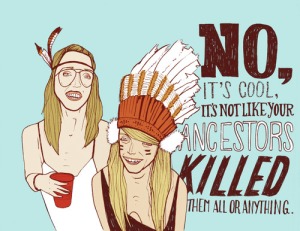

If settler radicals challenge their desires to live on Indigenous land, they also will challenge their desires to study, practice, or feel in any way linked to Indigenous culture. I am thinking here of Andrea Smith’s critique in Conquest of spiritual appropriation as a form of colonial and sexual violence. I also think of Waziyatawin’s statement to the Dakota Decolonization class of the relationship between Indigenous land and spirituality, which makes decolonization of land necessary to the practice of Indigenous spirituality. With these claims in mind, settler radicals must ask how their feelings of attachment to Indigenous land and culture enact appropriation and violence. Settlers are supposed to be people who connect to Indigenous land–the land where they were raised, or that they inherit after settling it–by studying Indigenous history and culture and linking it to their lives. Historically, non-Natives became settlers by adapting Indigenous dwelling sites, travel routes, place names, modes of gathering or cultivating food, and spiritual knowledges and practices.1 These acts are part of the normative function of conquest and settlement. Thus, decolonization does not follow if settlers simply study and emulate the lives of Indigenous people on Indigenous land.

Settler radicals desperately need to investigate this truth. It is relevant in particular to those for whom anarchism links them to communalism and counterculturism, such as in rural communes, permaculture, squatting, hoboing, foraging, and neo-pagan, earth-based, and New Age spirituality. These “alternative” settler cultures formed by occupying and traversing stolen Indigenous land and often by practicing cultural and spiritual appropriation. Their participants have imagined that they act anti-colonially by “appreciating” Indigenous culture or pursuing what they imagine to be Indigenous ways of life. But using these methods to try to be intimate with Indigenous land and culture expresses settler desires without necessarily contradicting them. Critiquing and separating from these practices may be necessary for settlers to commit to work for Indigenous decolonization.

This is a hard lesson for settler radicals to learn if they felt led to support Indigenous people by participating in “alternative” settler cultures. They must ask, then, if their interest to support Indigenous people arose not from an investment in decolonization, but in recolonization. Did they emulate, or impersonate Indigenous culture in order to gain the trust or affection of Indigenous people; in hopes, then, that they would gain access to the Indigenous culture or land that they, as settlers, actually desire? It’s twisted, but true: settler radicals may seek “solidarity” with Indigenous people by pursuing settler desires to possess Indigenous land and culture for themselves. If this is so, their supposedly “alternative” cultures present no alternative to the settler cultures that Indigenous decolonization will disrupt. All must be questioned if settlers are to commit to the work of Indigenous decolonization.

I write these brief thoughts in order to introduce and invite broader conversations whose complexity my words here have not begun to fulfill. My statements and questions mean not to limit conversation but to open it. I have asked settler radicals to continually pursue critical reflection that will un-settle their senses of self and relationship to place. I am playing here on multiple meanings in the word “unsettle,” notably its correlation with the word “displace.” Certainly, in this context, “unsettling” suggests the work of displacing settlers from their possession of Indigenous land. The word reminds settler radicals to divest of their desires to occupy Indigenous land in order to work for decolonization. But “unsettling” also can invoke the qualities that settlers try to avoid feeling, such as uncertainty, discomfort, and–in an emotive sense–displacement. Colonization is an ongoing process making settlers desire the certainty and comfort of emplacement. Such feelings are incompatible with the commitment to work for Indigenous decolonization. Embracing uncertainty and discomfort–getting used to these feelings, and learning to live well amidst them–will be the productive and enlivening result of settlers displacing their centrality on stolen land and committing to work for Indigenous decolonization.

~

1 Among the wide array of writing on these histories by scholars in Native Studies, my words here refer in particular to Vince Deloria, Custer Died for Your Sins: An Indian Manifesto (1969) and to Philip Deloria, Playing Indian (1998).

Throughout this essay, you seem to equate colonization with “emplacement” (the desire to be connected to the place where one lives), and that seems to be consistently presented as something that needs to be overcome, or gotten rid of. I totally reject this, unless such “emplacement” is clearly meant to refer to the desire to own a particular piece of land. I think the latter definitely needs to be overcome in order for a non-indigenous person to challenge colonization, but the former I think is an essential aspect of being a human animal that lives in harmony with the land and the wider community of life.

I have a sincere desire to challenge (and eradicate) colonization, and I see the process of unsettling the land (and my relationship to it and its native peoples) as a lifelong endeavor. To me, that endeavor is an essential part of rewilding myself and my way of life, dismantling civilization, and building the foundation for a new, healthy culture to replace it. But an even more essential aspect of all this is learning how to reconnect with the land and the wider community of life, spiritually (in our values and worldview) and physically (in our way of life). And what you seem to be saying is that not only is this not important for non-indigenous people to do, but that trying to do it on occupied land is what colonization is all about.

I completely disagree with this. I do not believe that settlers have ever had any intention of truly connecting with the land – their very way of life proves this, as they have consistently destroyed the landbase in order to “make a living” (logging, mining, agriculture, etc). Their actions in fact have (and still do) constitute a war on the land, and the desire to wage this war is exactly the driving force behind their war on the indigenous. In fact, I believe the settlers’ disconnection from the land is the root cause of their wetiko cultural disease, and I think overcoming that disconnection (through reconnecting) is exactly what is needed in order to get rid of the wetiko mindset.

What I do totally agree with is that settlers have always had a desire to OWN the land (in order to exploit it), and that desire definitely does constitute an essential aspect of colonization (the root of it, actually). Therefore, challenging colonization inevitably and fundamentally means challenging this desire for ownership, which in modern times manifests among most settlers as the desire to keep their house, their farm, their family’s property, etc. I agree that any settler who truly wants to fight colonization must give up any notion that they have a “right” to the land they “own”, and even that they CAN own the land (the concept of private property). I see that as step #1, with step #2 being recognizing that indigenous claims on the land supercede their own, and being willing to move if necessary.

If you practice your life in a directly accountable relationship to the Indigenous nation whose stolen land you occupy, then your effort to learn and live an indigenous relationship to that land may be in line with the work of Indigenous decolonization. You would only know if this is so if the people whose stolen lands you occupy tell you so. You can’t determine this for yourself, because you are the colonizer.

While I am not suggesting that you have done this, many settler radicals do: when you are unwilling to admit that you remain a settler-colonizer in the very act of trying to live in an indigenous relationship to stolen land, you craft an elaborate self-deception designed to protect you from taking full responsibility for your settler-colonial power — which includes your settler-colonial entitlement to choose to “be”/”become” “Indigenous.”

Waziyatawin makes the crucial argument in her article “Understanding Colonizer Status.” Speaking of Dakota and other Indigenous peoples:

“If we are struggling for Indigenous liberation on Indigenous lands, all people are going to have to practice Indigenous ways of being in some form. We will all need to engage in sustainable living practices and Indigenous cultures, including Dakota culture, offer excellent models for all people. That does not mean former-colonizers can appropriate our spirituality and ceremonial life, but it will mean they need to embrace Indigenous values such as balance and reciprocity.

In the meantime, it is far more appropriate for colonizers to work to ensure that Dakota people are able to practice Dakota ways of being. If you believe sugar-bushing and wild-ricing are important, than help Dakota people recover lands so that we can engage that practice. Perhaps, we can eventually engage such activities together.”

Clearly, there is room in Waziyatawin’s formulation for colonizers to learn ways to live in responsible relationship to Indigenous peoples and Indigenous lands. Nothing in my writing, or my comment here forecloses this.

My intention in my essay was to encourage critical self-reflection: a practice Waziyatawin requests of colonizers, and that my essay practices as a response to her and other Indigenous leaders. Your words suggests to me that you have begun a process of critical self-reflection, but that you might want to allow that process to continue and deepen. My simple warning to radical settlers remains: do not deceive yourselves into thinking that your radicalism liberates you from being a colonizer. You may be, in Memmi’s sense, a self-negating colonizer. But, following his formulation, nothing that you choose to believe, learn, or practice — even and especially your radicalism — ever separates you from being a colonizer: and, as such, capable of reproducing colonization — even, and especially *through* your radicalism.

Under what conditions does “re-wilding” yourself reproduce settler-colonizer power, against the stated demands of Indigenous peoples? What conditions would have to obtain for “re-wilding” yourself to be responsible to and consonant with Indigenous decolonization?

You cannot answer these questions for yourself or by only speaking and listening to other settler-colonizers. Please learn the answers to these question from within a long-term, accountable relationship to Indigenous people pursuing decolonization — who are *not* responsible for answering them for you, but to whom you must be in responsible relationship when you do.

I wrote my reply to Jessica, above — and my earlier essay — as words spoken to non-Indigenous people as settlers, while speaking as one myself; and I replied in this way because I understood from your post, Jenny, that you recognize yourself to be a non-Indigenous person and a settler. While this may be clear when the pieces are read in sequence, I add this note so my Indigenous readers know that my reply does not invoke you in my use of the pronoun “you”; rather, in the reply, I use “you” to directly address non-Indigenous people as settlers.

Thank you Scott for this deeply thoughtful call for settlers, like myself, to engage in a process of reflecting on ‘radicalism,’ to discover whether or not it’s truly radical as definated by front line communities, or if it’s a form of radicalism which responds to white, middle class, hetero, suburban culture in ways that replicate much of these ideologies and practices. As someone who does Indigenous support work, most directly as a collective member of Black Mesa Indigenous Support, I’ve had my ideas of home, connection to land, ancestry and spirituality drastically relitivized and altered by working in support of Indigenous communities fighting for cultural and literal survival in the face of continued forced relocation and genocide. What does it mean to learn the plants of the northwest where I grew up and feel a sense of connection to the forest and especially wilderness, when the wilderness itself is a construction set in contrast to civilization and only exists as a result of genocide and the ’empyting’ of land? My connection to land and particularly to a history of that land and a way of life truly in balance with that land is about as deep as the topsoil that washes away in the first fall deluge.

As someone who wants to live rurally again some day, I think about rural organizing and how threatening these questions of entitelment to land and identities to land based living will be. I think about the homesteading movement and how even the unchecked language continues to romanticize settle colonialism and the theft of Indigenous land.

The world of primitivism, when disconnected from relationships to Indigenous resistance and other people of color led struggles for liberation, replicates a kind of entitlement to Indigenous land, skills, spirituality… which as you’ve pointed out is really settler colonialism with a buckskin mask. I think it’s interesting that I’ve heard the particular form of U.S. anarcho primitivism came out of Minnehaha Free State which was originally an alliance between earth first minded folks, AIM and other community members. White radicals were engaging in collective struggle with Indigenous folks and at times were invited into different cultural and or spiritual practices. As primivitist culture evolved it in some forms held on to those spiritual and or cultural practices but lost the context of relationships to Indigenous people and their struggle for land and soveignty. We lose our own context and sense of history and where our movements come from so easily, of course it’s part of how we as white folks are raised to survive and perpetuate whiteness.

The question I would like to add is how do I encourage myself and other white folks to examine our desire for connection to land and land based spirituality to see if it reinforces the settle colonial mentality while recognizing that white folks desperately need further connection rather than a deepening sense of alienation and despair which results from white supremacy, individualistic, heteropatriarchial, capitalist, colonial culture. How can deeper connection to land, plants, animals and each other based in balance, reciprocity and revolutionary love not be based on continued entitlement/appropriation/theft of Indigenous land and spirituality?

I’ve been thinking and writing about the ways in which settler radicalism as you have aptly named can replicate white supremacy, patriarchy and colonialism. I’ve been thinking particularly about how anarchist subculture, often white anarchists are the ones doing Indigenous Solidarity and support work and what the impacts of unquestioned ‘settle radicalism’ might be in terms of how the conversation about Indigenous support is so often shaped by white folks not often in conversation with other movements led by front line communities/people of color. Also how settler radicalism sometimes comes with values that maintain white supremacy: entitlement, righteousness, seeing things in terms of black and white, coming from a place of anger, centering ones own experience/ideas of radicalism in ways that can alienate other people of color and or white folks wanting to be more involved supporting Indigenous resistance. Another question is how can we as anti-racist white folks, anarchists, enter whatever identiy here, be a part of building a movement for decolinization and liberation that doesn’t deepen divisions between movements people of color led movements which were created by white supremacy in the first place. How can we recognize the role disconnection from land, spirituality, mutualism, our bodies, each other plays in creating settlers in the first place and begin the work of healing, transforming, decolinizing with out continuing to benefit from, ignore or perpetuate the disconnection/displacement Indigenous people are currently fighting? I know a lot of these are questions Scott was posing but I wanted to reframe to acknowledge the work we as white folks have to do to truly connect and resist in ways that don’t perpetuate systems of oppression. As someone who is also involved with communities most impacted and fighting for migrant justice and prison abolition and someone who spends a fair amount of time in cities, I think it’s important to ask who gets to learn these land based skills, who gets to survive? How do we learn and teach and live in ways that mean we’re working for everyone’s survival, not just those with enough privilege.

Reblogged this on Many Politics and commented:

Check out this short essay by Scott Morgensen on settler desires for indigenous lands… he implicates permaculture, New Age spirituality, and other “alternative” settler cultures in the desire to appropriate indigenous land and cultures.

He also gets challenged by another settler, who argues for the importance of connecting to land and place. Morgensen’s clarification: “If you practice your life in a directly accountable relationship to the Indigenous nation whose stolen land you occupy, then your effort to learn and live an indigenous relationship to that land may be in line with the work of Indigenous decolonization. You would only know if this is so if the people whose stolen lands you occupy tell you so. You can’t determine this for yourself, because you are the colonizer.”

I’ve been working through these issues myself, especially now that I’m back in school researching food sovereignty and other alternative food movements in North America. I haven’t gone very far yet, but what’s immediately clear is the absolute lack of writing and thinking about the relationship between settler food movements and colonialism. There’s some writing about indigenous food sovereignty, and writing about ‘food justice’ that addresses institutional racism, but very little (actually pretty much nothing) that I’ve read has sought to address the challenge that Morgensen is raising here to settler alternative food movements.

Pingback: Settler Colonial Food Movements? | Food and Land

Reblogged this on Corey Snelgrove and commented:

Add your thoughts here… (optional)

Pingback: Decolonization and Unsettling Settler Privilege | Decolonization

I am a white settler and a colonizer, I am a 61 year old working class disabled lesbian grandmother. I have been involved in a variety of consciouness raising issues over the last 43 years. Feminism and womwn’s rights, gay rights, anti racism work, peace marches, environmental concerns. I feel that all of these issues are connected and it was a process of learning that has brought me to where \i am now. I have had a spiritual calling to now be involved in decolonizing myself, unsettling the settler and being involved with first nations struggles which I do see as concerns of everyone to a point. I do feel that I actually am not entitled to be living in this country.

Leaving this country at this point in time is not an option for me due to finances. I do feel that it is my responsibility to take positive action to further first nation struggles for nationhood, land, self government and do this without burdening first nations people with my ignorance. I am self educating myself constantly. I rarely feel guilt or shame for being a settler colonizer but see it as an opportunity to try to make a difference in my various communities that will further first nation concerns. This is because of my work in the past from both side of an issue where there are those with priviledge over others . My age and life experience has brought me to this point. However, all that said I am learning and unlearning daily and sometimes learning occurs from mistakes. I try to not be to hard on myself for my mistakes as my history with this is that I tend to take to much responsibility. I also think that I owe the original people of this country for how much my settler family has prospered over the years at the cost to first nations people. If I would leave the country now, my responsibility would not end. How effective would I be trying to decolonize or support decolonizing Canada from England? I believe that this is a spiritual movement as it is about the land and the original people who looked after the land and and the water and all therein: their spiritual beliefs are all tied in with this. I do appreciate these articles as they have pointed out to me the dangers and hazards of settlers supporting first nations. There really is no one way or only way to participate in this movement. Each one of us is responsible for determining what we should be doing or not be doing and how. Acting or do anything without connection to a first nations group or organization is risky.For me this means staying connected to spirit keeping me heart, eyes and ears open, and speaking only when I have something worth saying. I find that if I talk about a new learning too soon, it takes too many words. Once I have internalized this new learning I can speak

about it with few words. Really valuable knowledge actually invovles the use of few words, the less the better. This is something that academia would do well to acknowledge. I challenge univerity students to submit one page when 40 were called for and then justify this piece of writing as direct and to the point and communicates valuable knowledge in a language accessible to many. (Of course my comments here do not meet this criteria) I do appreciate how the left wing white activists, anarchists are being called on their settler/ colonizing priviledge. Here in Victoria, this group has struggled with and still does not have a formal relationship with first nations. This is due to lack of knowledge about the protocols of the first nations people here in Victoria.

Reblogged this on Divest Uvic and commented:

Questions. where have all the questions gone? critical reflections?

Questioning our work to inform what comes after it is a good start to understanding the reproduction of violence. Questions!

I was a 30 year-old not-yet-self-identified settler radical when I began to consciously explore my connection to other life forms, and to seek out other anarcho-primitivists desiring to live out blissful, pristine utopian existences beyond our wildest dreams. After nearly 3 decades of abuse, addiction, physical disability and mental illness, I was just starting to enjoy life and envision a future for myself! So when I noticed that mostly only other white, class privileged people were available for and even considering such plans, I had to ask myself what was going on here. Why wouldn’t everyone want to get out of the city and live off the land? Realizing that a lot of people didn’t seem to have much of a choice, and that the entire social-political-economy was based on this fact, led me to question my entitlement to “wilderness” and “nature” experiences on this continent. Coming to terms with being a settler in an oppressive system I neither chose nor desired, I felt angry, cheated and victimized. Although it has been my reality for many years, suffering in the nearly total alienation of cities is not a life worth living to me. It never was, and now that I am capable of actually being present in this world, it is intolerable. For me, feeling desperate to escape and undermine this techno-industrial hell, while recognizing that I have no right to get in touch and bond with stolen land, has forced me to embrace an often overlooked aspect of what it means to be alive and to experience connection with the Earth: Death.

My perspective is informed by what it means to me to recover from the dominant culture. As I see it, the problem with civilization, at its root, as well as its many manifestations, is that it is fear-based. Fear of death, of uncertainty, of insecurity, of not being in control, of not having enough, of being at the mercy of a power much greater than themselves, is what led folks to plant those first seeds, to tame those first animals, paving the way for all the domesticating and dominating practices that followed. Of course, this sense of security has always come at a cost to others’ lives, safety and freedom. The greed that drives Progress, undermines indigenous rights and destroys ecological integrity is the obsessive-compulsive avoidance of death, illness and injury. When we as settlers talk about our feelings of entitlement to land, we are talking about an emotional attachment to life itself. We are talking about cultural values inherent to civilization, which transcend and encompass many subcultures, “alternative” lifestyle practices and political movements. Part of living is dying, and in spite of their best efforts, white middle class people eventually die. The perfectly natural and inevitable process of death, wherein the bodies on loan to us in this lifetime mix with the soil, break down into elements and take shape as new life forms, is essentially as full of life as communing with redwood trees, swimming in lakes and picking wild blueberries by the coast. We are life. We are nature. We are the Earth. Matter and energy can not be destroyed, only transformed.

Nature is unpredictable and it is up to each one of us to come to terms with our losses. Let me be clear: I am not saying that people who are oppressed should find “meaning” in the death and suffering among their communities, not feel angry about it, and stop fighting. People who have suffered oppression have had to develop more than their fair share of patience and tolerance for the unfair conditions of life imposed upon them by a patriarchal, white supremacist, ablist, homophobic, colonial system. I am speaking to the parasitic folks who irrationally fear the end of life, who assume entitlement to life even when their lives may actually serve no positive social or ecological function beyond respiration, digestion and death. I am saying to the greedy ones who grasp for land while other people having enough food and shelter, who survive on the fetishization of human life and who profit from a culture of fear. Let go and let nature do its thing. Who knows – it may be your time to die, or maybe you will have the courage to change in time to be useful to the people who belong on this continent. All I know is that I could not be happy for as long as I limited my idea of nature connectedness to my current human form. Irrationally fearing the end of life, refusing to surrender my claim to stolen land, was actually as hellish as city life itself. Fear is hell. For radical settlers to confront the heartbreaking reality that most surviving indigenous people must live in cities, on shitty land, in horrific conditions, or not at all, is to relieve themselves of the burden of justifying their privileged access to the wilderness.

Another dimension of this is that there are way too many of us humans to support ecological balance, so losing our fear of death helps us to confront overpopulation honestly. I know that my biomass could be put to better use than in its current human form. I won’t waste my life in a hospital to avoid death any more than I would pursue formal education to ensure my financial security. I won’t protect my life at the cost of having a life worth living. However, I am not “suicidal.” As long as I am alive, I want to fully commit myself to decolonization at all costs, to the ongoing process of un-learning and of reconstructing a saner society. The truth is that I am only alive today because of being a white, middle-class, mostly able-bodied settler in a racist, classist, ablist, colonial system. The system is merciless and has only allowed me to live because I have not yet posed a serious threat to it. Because of my role as a settler in this lifetime, my devoted connection to the Earth and all living things seems most appropriately directed as a willingness to fight alongside indigenous people for decolonization and against the machine of Progress, even if, and when, it costs me my life. I am studying what it means to be an ally to indigenous groups and to the Earth look forward to offering my time, energy, money, and my life itself in the fight for a life worth living – for all of us, or none of us.

Pingback: Understanding Oppressive Practices for Social Innovators | DISRUPT MGZN.

Pingback: On Refusal | Decolonization

It is amazing when younger generation step in and start to going back to their roots. Some doen’t care anymore to go back to their ancestor way and prefer the future than the fast. I hope you guys keep it up and live like the ancestor does hundred of years ago.

Pingback: Decolonizing the Mosque I: Colonial “Canadian-ness” among Muslims – Identity Crisis